by Shannon Schubert | @Shanschubert

Trigger warning: Suicide, self harm and mental illness are discussed in this article.

One in five Victorians will experience a mental health condition each year. In August, the largest national survey of youth mental health in Australian history, revealed one in seven children and young people experienced a mental health disorder in the last 12 months. This is equivalent to 560,000 young Australians.

In response to this, the Australian government said they were working with states and territories on “significant, long-term reform” in the mental health sector.

State mental health services are broken up by area. There are 13 metropolitan and eight rural areas providing three streams of mental health services: Child and Adolescent, Adult, and Aged Persons Mental Health services. Within each stream there are Hospital Inpatient Services, Community Mental Health Services and Residential Services for the aged.

Professor Patrick McGorry, executive director of Orygen and Professor of Youth Mental Health at the University of Melbourne, said the public mental healthcare system has been in disarray for the last five to ten years.

“The problem is the system has increasingly shrunk, rather than grown (over the last decade),” said Professor McGorry.

He believes short-term “Band-Aid fix” announcements made by state governments fail to address the root of the problem and the increasing demand for care.

Brydie, a 19-year-old former public mental healthcare patient, said these services fail to see the urgency of mental health conditions.

She said no matter how much she expressed her poor mental health, nothing was said or offered to her except a trial on different medication.

“The Andrews Labor Government is committed to providing support and services to people with a mental illness and their families,” Victorian Minister for Mental Health Martin Foley said of the state government’s commitment to improving services.

Brydie said her negative experience revolved around the “in-and-out” nature of public mental health care services that are underfunded and under facilitated.

One of Brydie’s worst experiences at a public inpatient stay service was sharing a room with someone who experienced night terrors.

“I was suffering insomnia and sleeping was very difficult at the time, and I would finally get to sleep then my roommate would have night terrors and begin screaming less than a metre away in the middle of the night.”

She said this made her very distressed: “14 beds is clearly not enough for the amount of people with significant mental health issues in the area”.

The lack of beds and high demand mean an 18-year-old can be put in a room with a 12-year-old. Adolescents with completely different mental disorders could be put in a room together, Brydie said.

“You’re feeling shit, you’re in there, there’s no therapy and then you see things like a 14-year-old schizophrenic having an episode and being sedated,” she said.

“It’s obviously going to make you feel worse.”

Professor McGorry said people are suffering, but there is not a strong enough public voice to apply the pressure needed on state and federal politicians.

“My depression, anxiety, insomnia, self-harm, suicidal ideation and thoughts, and a minor psychotic episode were not taken seriously enough,” Brydie said.

She summarised her family’s thoughts on public mental health care as a “Band-Aid solution”.

The consultation phase has closed for the state government’s 10-year mental health care strategy. The 10-year plan is to include funding for services specific to indigenous peoples, the LGBTIQ and the Culturally And Linguistically Diverse – or CALD – community.

Improving early mental health assessment and reducing preventable emergency department presentations and inpatient admissions are also on the agenda for the state government.

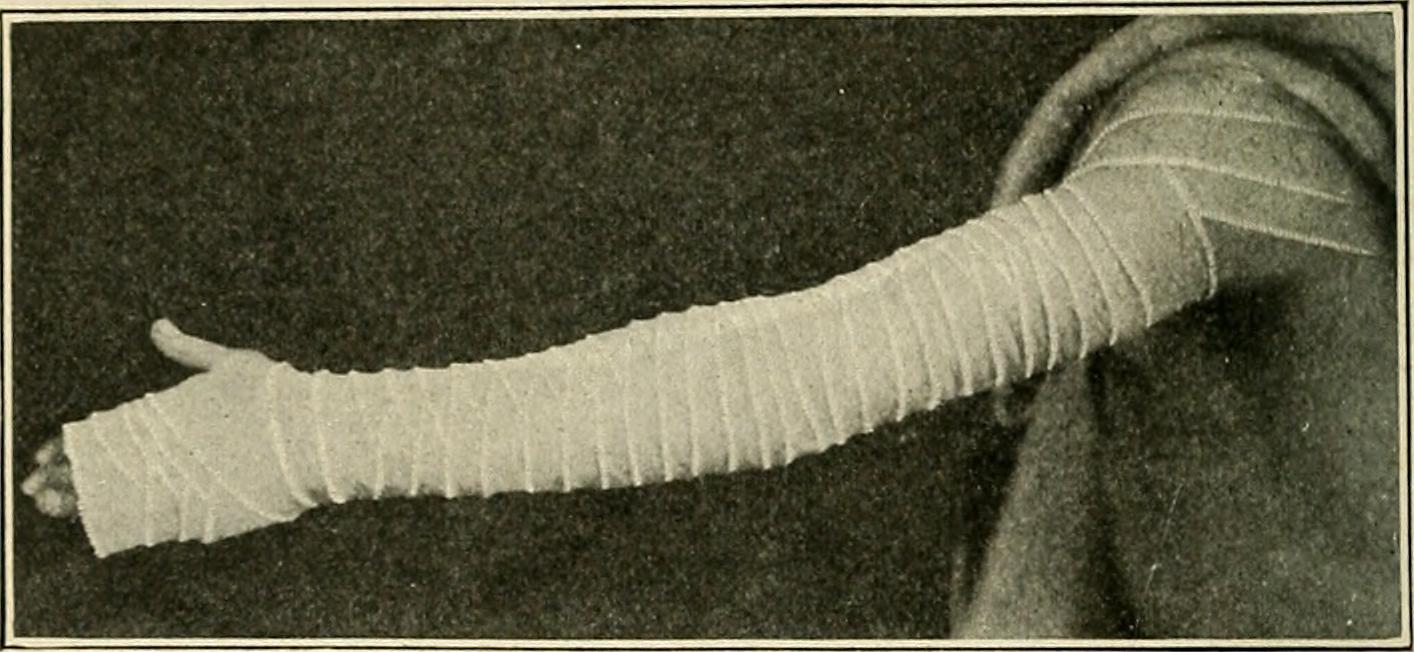

Brydie’s condition worsened over her time using public mental healthcare services. After numerous suicide attempts and needing to go to the emergency department for stitches due to self-harming, she switched to private services. The improvement of her mental healthcare over the last year confirms what her family suspected about the ineffectiveness of the public system.

Professor McGorry said other states have similar issues, however where Victoria used to lead the pack with the highest spending per capita in 1992-93, it is now clearly behind, spending the lowest per capita in mental health funding in 2010-11.

“We’re rebuilding the mental health system, [we’ll] have a 10-year plan by year’s end and we are funding projects and services that will help fill the gaps and meet the demand in mental health catchments across the state,” Minister Foley said.

The state government needs to do more than provide a piece of paper, Professor McGorry said, with “funding, funding, funding” the only way to fix the deteriorating system, which must be made a priority.

He said there are not enough politicians championing the cause of mental health.

“We need to adopt a similar attitude to the roadtoll, the recent ads from the government say ‘0 lives’, we should adopt the same attitude for suicide prevention.”

“Something has to be done.”

If this story has affected you, talk to a GP or health professional, or contact one of the following resources:

SANE Australia Helpline – Ph: 1800 18 SANE (7263) – www.sane.org

Lifeline – Ph: 13 11 14

Headspace – Ph: 1800 650 850 – www.headspace.org.au

ReachOut – www.reachout.com