Have you ever wondered why there are so many Boundary roads throughout the larger cities within Australia? Boundary roads are a remnant from our colonial past, which was characterised by the subjugation of Aborigines to the implanted government, police forces, schools and churches. The lasting impacts of this domination upon the collective consciousness of an entire population aren’t regularly discussed in today’s society.

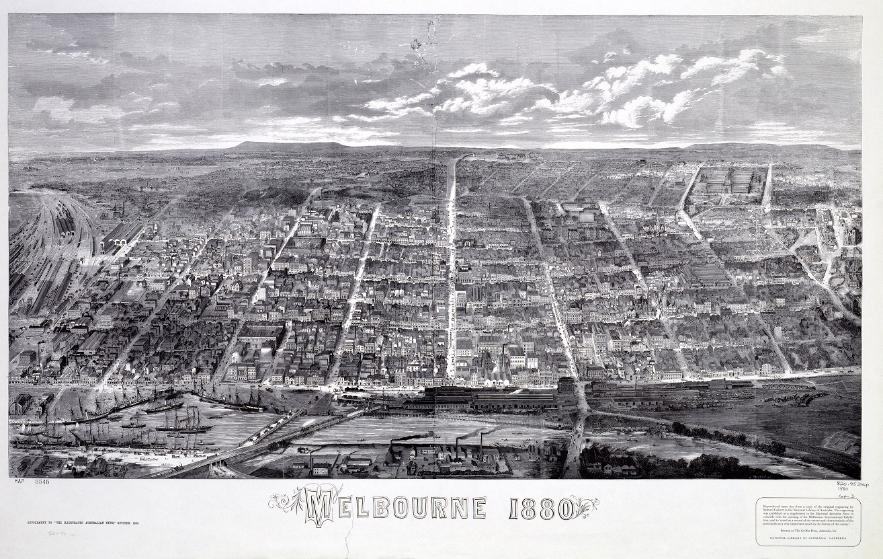

During the mid-1800s, in various settlements across the country, laws were passed which established boundary lines for the purpose of better aligning the streets and regulating the local police forces. In effect, these laws allowed curfews to be placed on Indigenous people, which exiled them outside the boundary lines of various towns. Brisbane has the most Boundary roads out of any city in the country; the Police Towns Act of 1839 allowed police to ride through towns on horseback at 4pm every day, cracking stockwhips as a warning for Aboriginal men, women and children to leave. On Sundays, Aboriginal people weren’t allowed to enter within the boundary lines. This inhumane treatment was justified in the Act under the heading: “Removing and preventing nuisances and obstructions”.

When non-Indigenous Australians learn about this history, feelings of ‘white guilt’ may be deepened, whereby people feel guilty for the ongoing impact of colonisation on Aboriginal Australia. In turning this guilt inwards, non-Indigenous citizens often feel powerless in contributing to reconciliation efforts. It is understandable why many non-Indigenous Australians experience both individual and collective guilt; it is overwhelming to learn that the nation we call our own has been built on land acquired through the genocide of an entire race. But ‘white guilt’ is often self-indulgent and unproductive, as it focuses on receiving forgiveness from Aborigines as opposed to developing a collective responsibility and consciousness for positive change.

This is why calls for local governments to rename Boundary roads are not useful, as it has the effect of airbrushing history to ease the discomfort of those non-Indigenous Australians who know what these streets historically represent. Across the country, many Indigenous Australians have reappropriated Boundary roads, and changing the name would only have the impact of weakening this empowerment and ownership that the streets now represent. A more constructive approach would be using Boundary roads as an opportunity to educate one another in the spirit of reconciliation, so that we may further break down the barriers between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

But when are place names or expressions not able to be reappropriated? Dr Gary Foley, Aboriginal Gumbainggir activist and writer, has detailed how the University of Melbourne has failed to address the concerns over buildings named after historical figures who have proven to be offensive to Indigenous cultures and peoples. Among them is the Richard Berry building, named after the Professor of Anatomy at the University from 1903 to 1929. Berry was influential within social and political circles in Australia, campaigning for the legalisation of eugenics. This idea is often connected to ‘white Australia’ policies, assimilation, and the removal of Aboriginal children from their families. At the height of the eugenics movement in Victoria, The Mental Deficiency Act was passed in 1939, which aimed to institutionalise and potentially sterilise people and groups within society deemed ‘defective’. Due to the racial superiority values prevalent within society during this time, the Indigenous population was included among the groups covered under the Act. Thankfully, the law was never enacted due in part to the lessons learnt from the Holocaust.

The process of digging through the not-so-distant colonial past can be painful and difficult, but it is necessary to understand the current social conditions. On an individual level, it is easy to put Indigenous issues in the too-hard basket. However, each of us should strive to contribute positively to reconciliation.

As a student, the most valuable contribution you can give to the reconciliation effort is to educate yourself on the historical, political and socio-economic issues facing Indigenous Australians. While there are various ways to seek out information independently, you may decide that this learning process is best supported in a university environment. If so, elective study courses are on offer relating to Indigenous studies in the fields of health, policy, human rights, environment, culture and planning. If you are looking to develop a more rounded knowledge of Indigenous issues within a global and Australian context, undergraduate students can opt to complete the Indigenous Specialisation. This initiative is available to all undergraduate students who have four electives available within their degree specialisation structure and can be completed regardless of your primary program of study. Students who complete four Indigenous-themed electives will receive formal acknowledgement of this specialisation on their academic transcript.

Participation in volunteering programs, such as the Australian Indigenous Mentoring Experience (AIME), is invaluable to the reconciliation progress. AIME connects university students with Indigenous high school students in a structured education program. AIME has proven to be successful in boosting students’ self-efficacy, with their 2012 Annual Report stating that the Year 9 to university progression rate among participating students was 22.1 per cent – nearly 6 times the national Indigenous average of 3.8 per cent, and approaching the national non-Indigenous average of 36.8 per cent.

By taking individual responsibility for Indigenous and non-Indigenous reconciliation, and building upon a connected and hybridised history, we can begin to belong to a shared future with diverse collective aims and aspirations.

Kathleen Feain