When I was young I thought all adopted children were like Cinderella; in a horrible situation they needed to escape from. Then I found out my Mum was adopted and I was a little confused.

Australian media generally didn’t help. Adoption is often only portrayed in one of two ways.

The first would be in tabloids and trashy mags. Whenever there’s an adoption in Hollywood, these magazines battle to be the first to publish pictures of the children and gush about how saintly these parents are for having given someone else’s child a better future. For a while, adopting a child from a third-world country seemed to be the new accessory. Celebrity couple Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt have adopted three children from three different countries, and have said they’d “never say no” to adopting more.

This side of adoption in the media is obviously just frivolous entertainment for when we sit by the pool or get a pedicure.

The other aspect of adoption we are exposed to, however, is completely on the other end of the spectrum. Way on the other side, toppling over the edge, barely even on the same spectrum it’s so opposite. It’s forced adoption.

Occurring from the late 1950s to the 1970s, there was a practice of forcing new mothers to give their babies up for adoption. The most common method was “the bullying arrogance of a society that presumed to know what was best,” former Prime Minister Julie Gillard stated in her national apology to the victims of forced adoption last year.

Another dark part of Australian history was the forced removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families, a practice which occurred between the late 1800s and the 1970s, the victims of which later became known as the Stolen Generation.

With the media’s portrayal of adoption being generally either one of the two extremes; devout charity or atrocious chapters of Australian history, it’s no wonder people are surprised to find adoption in their own neighbourhood, and often don’t know how to react to it.

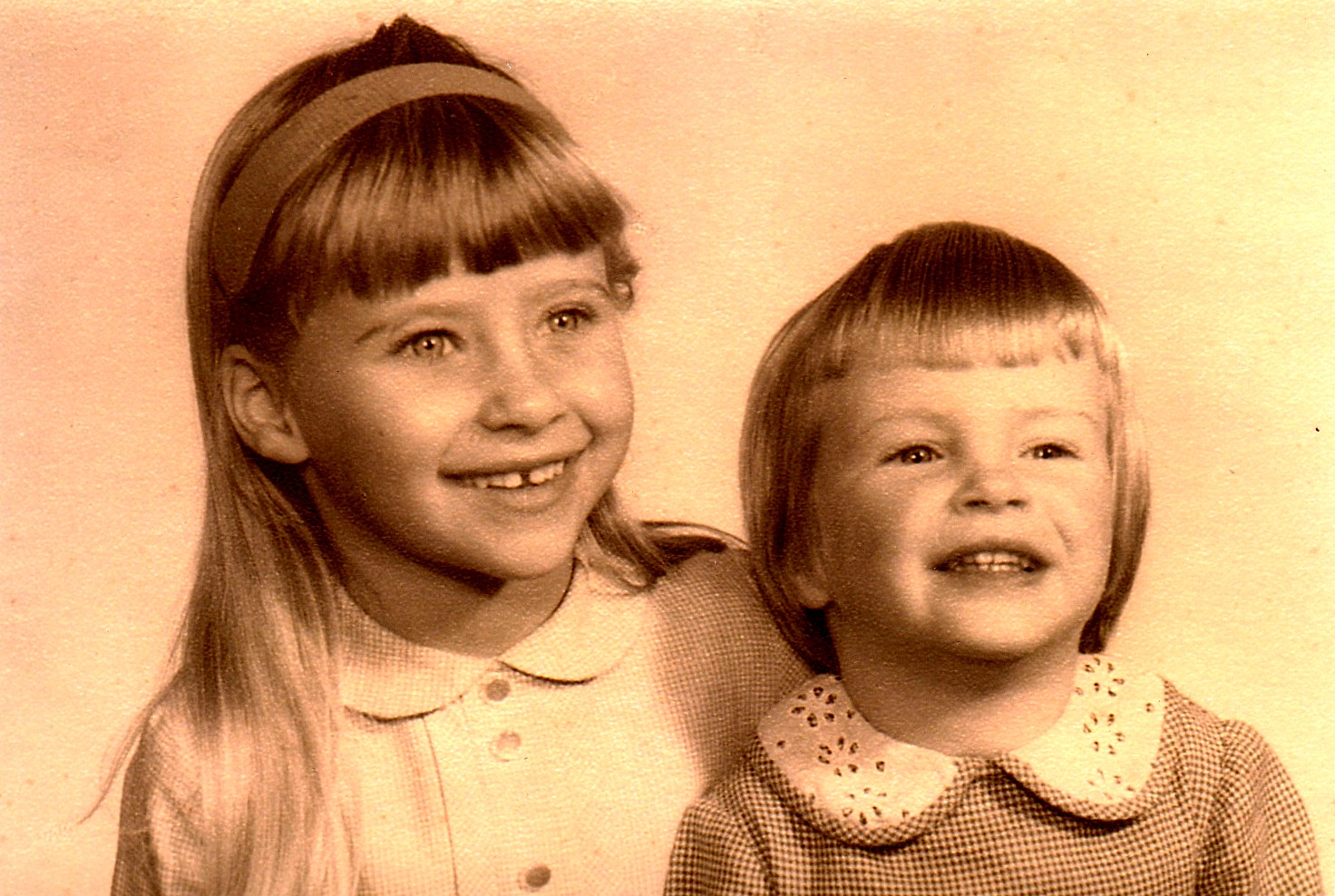

My mother, Annabel, grew up in Brighton, one of the typically well off suburbs in Melbourne, with her older sister Susan and her parents Judy and Doug. They always knew they were a bit different, Susan had a much more European look. She would tan during the summer while my Mum was slathered in SPF 30+ every day of the year. My mum also has a very…distinguishable nose, which she didn’t share with any of her family. But it wasn’t until they had the “where do children come from” talk they realised what being adopted meant; that their Mum and Dad weren’t biologically related to them. Through her teenage years, Susan would use her adoption as a weapon; “you can’t tell me what to do anyway, you’re not my real parents.” Not the usual excuse in a teenager’s hissy fit.

Annabel dreaded visits to the doctor, where her mother would respond nervously and anxiously to questions regarding her genes.“I just didn’t want it brought up,” Annabel said, “It wasn’t shame, but people would be surprised and struggled to know what to say in response, so everyone was embarrassed together. When it was brought up, it was just another reminder of this ‘difference’ never discussed or acknowledged, and certainly never dealt with. Everyone was happier pretending it didn’t exist.”

She had always known she would search for her biological parents eventually, but it wasn’t until she was 24 with a steady job she started looking. Judy seemed hurt and surprised my mother was doing this, but Doug was more accepting; “he saw the logic of it.” It still wasn’t discussed though, and Susan didn’t do the same until she was 40, with the help of my mum.

Thanks to the 1984 amendment to the Adoption Act (effective 1985), adopted persons have the right to access information about their adoption. Mum couldn’t just Google her family tree like we can now so she contacted an agency called Birthlink. It took five months of searching through documents to find her biological parents.

They lived in Essendon. After giving my Mum up for adoption, they later married and had two more children, who they raised together. Her biological parents weren’t particularly happy to be contacted by her. They eventually agreed to meet her without their children knowing. “She cancelled once because her daughter was unexpectedly at home”. Mum was told about the family, “as if providing facts to a researcher”, but only out of obligation. They acknowledged she had a right to know this, but did not welcome her in anyway, cutting off all contact after their first and only meeting.

Eventually one of their other children contacted my mum. I remember once a year going to his house for lunch, though I never really wondered why my Nanna wasn’t coming or why Susan didn’t ask about them. They were nothing but polite to me, both had recently been married and had their first children with their spouses, so I was just happy to have some babies to play with.

“I felt they thought I wanted something from their family,” my mum told me. Neither was open about my mum with anyone else, so they could continue she didn’t exist, just like their parents still do. “Eventually, I went away. It doesn’t take much to make an adopted person feel rejected.”

There still exists a stigma attached to being adopted. When speaking to an adopted person, or their family, often people can be insensitive to the complexities involved in adoptions. Sometimes, it seems wider society only views adoption through the lens of the media and therefore sees it as a great tragedy, or a sensational saviour. But in many cases, it is neither. Both my Mum and Aunt Susan are still asked, “Do you know your real parents?” Susan, now 53, still gets told, “You don’t know how lucky you were, your parents must have been saints!”

Adoption isn’t always a righteous good deed in the public eye, and it isn’t always a horrific crime. Sometimes it’s just your friendly neighbourhood family of four.

By Tess McLaughlan

Image: Susan (left) and Annabel. Picture supplied by writer.