by Louisa Keck | @LouisaKeck

“What does Bill Shorten actually believe in?”

“Well, the Labor Party believes in lots of things and it’s a great opportunity this morning to talk about some of them. What I fundamentally believe and I think it was Martin Luther King who said this best, but it’s, I think true then and it’s true now, is everybody is somebody. I believe in a chance where everybody gets the chance to fulfill their potential, where we are not a divided society but we’re a united society.”

Falling short of likening the leader of the opposition to the girl from Mean Girls with all the feelings, this jumbled mess of a response to a question asked by Jon Faine on live radio earlier this year may point to something deeper than simply ammunition for an Andrew Bolt column.

The media has spent the last month dragging up the dirt on Bill Shorten’s personal and political past, going so far as to report on the politician’s change of AFL teams in the 1980s, but it’s Shorten’s striking lack of political ideals that remains startlingly clear. As Janet Albrechsten writes in The Australian, after a nine-year career as a union leader and almost eight years in parliament, Shorten has been totally unable to demonstrate any particularly defining characteristics or carve a strong and respectable persona for himself in the public eye. As Shorten churns out political rhetoric and nonsensical regurgitation of the party line, understanding exactly what Shorten believes in continues to elude voters from both sides of Australian politics.

It would appear instead that Shorten is prepared to use whatever tactic needed to get what he wants, whether it means adopting policy, charming political enemies or burning allies. All Shorten really seems prepared to fight for is achieving his own political success – at whatever cost that may be to his country or his party.

However, Shorten is not in the minority within Australian politics, as the worrying trend of electing career politicians continues. Instead of electing experienced, diverse and intelligent leaders from other sectors determined to make a difference, we are too often left to choose between candidates who represent nothing more than their own personal ambition. Without strong morals and ideals to provide an anchor in moments of duress and negotiation, it’s not difficult to understand how the policy proposals that may have pushed one candidate over the line at election time can become morphed and sidelined.

In The Mask of Sanity, researcher Hervey Clerckley wrote the three core characteristics of psychopathy – egocentricity, lack of remorse and superficial charm – could be found in nearly all areas of life, including politics. A 2012 article in The Atlantic stated research showed a number of advantages that make psychopaths particularly suited to life on the public stage as “psychopaths score low on measures of stress reactivity, anxiety and depression, and high on measures of competitive achievement, positive impressions on first encounters, and fearlessness.” Several studies and books like Snakes in Suits by Paul Babiak and Robert Hare, and The Psychopath Test by Jon Ronson have speculated on the high level of correlation between CEOs and psychopaths, based on their greed for power and ability to make decisions at the expense of others for the purpose of personal gain.

It’s not a far stretch to apply this same theory to politics, as we are exposed again and again to leaders who will do whatever it takes, by hook or by crook (to borrow from our current PM), to remain in power. The pressure and constant scrutiny that come with the profession are unimaginable to the average Australian, and it takes a very particular personality type to take that on from the outset.

However, being quick to label all politicians who fail to exhibit much of a backbone as psychopathic has the potential to trivialise a much larger issue. Politics is a game of compromise after all. Peter Garrett serves as a prime example of just how fickle a game it can be. Before entering politics, Garrett was the lead singer of Midnight Oil, president of the Australian Conservation Foundation, Greenpeace board member and advocate for aboriginal land rights. Environmentally minded Australians were rubbing their hands together in glee, a man so full of passion and ideals had arrived to finally make a difference. Yet not long after, Garrett was forced to make decisions that angered the campaigning activists among whom he was once a hero, all part of the balancing act of sticking to party obligations.

The jury is still out on Shorten and precisely where the blame lies, as we see with Garrett. The media, the individual, the political machine and the demands of society all play their own part in the deterioration of political integrity and idealism. Shorten was instrumental in the introduction of the National Disability Insurance Scheme, evidence he may have what it takes to become a conviction politician after all. We must support our politicians in their attempts to demonstrate integrity despite the scrutiny and compromise, rather than shaming them for conforming to what the role requires.

As disillusioning a picture this might paint of the Australian political landscape, we have only to look to the United States for the example set by President Barack Obama, a man who at the very end of his leadership is stopping at nothing to push through the legislation he was most passionate about right from day one. Though a rare breed, somewhere in the wild politicians who are willing to tolerate the intense scrutiny inherent in contributing positively to society, still exist; rather than those who are primarily motivated by power and control.

The media eventually depicts a striking contrast between the ego and the idealist, and through the lens of history we will be able to look back on the leaders who helped to shape the world and those who simply worked to stroke their own ego.

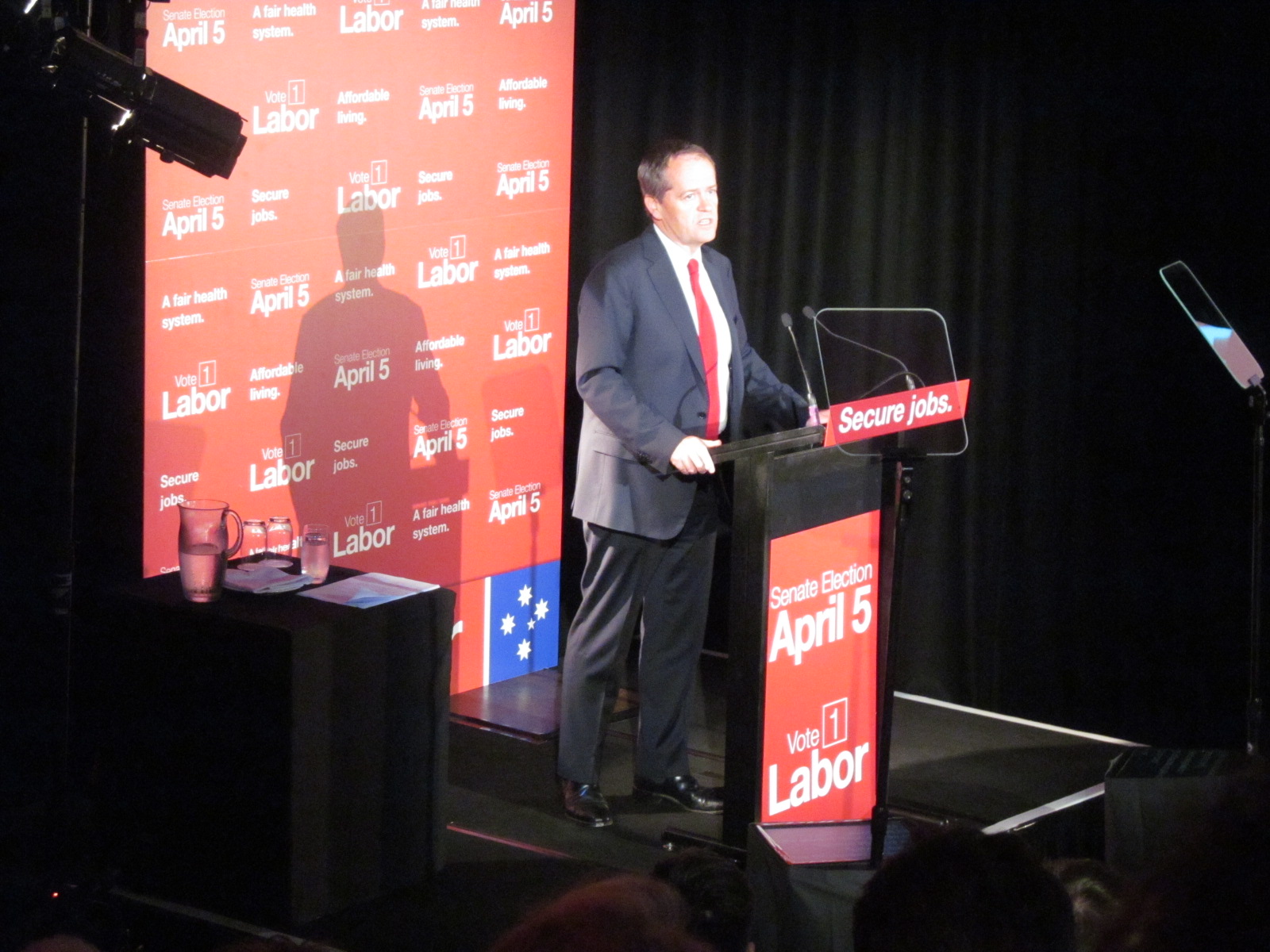

Image source: Orderinchaos / Wikipedia Commons