Words by Sarah Krieg

Image by John Barrett

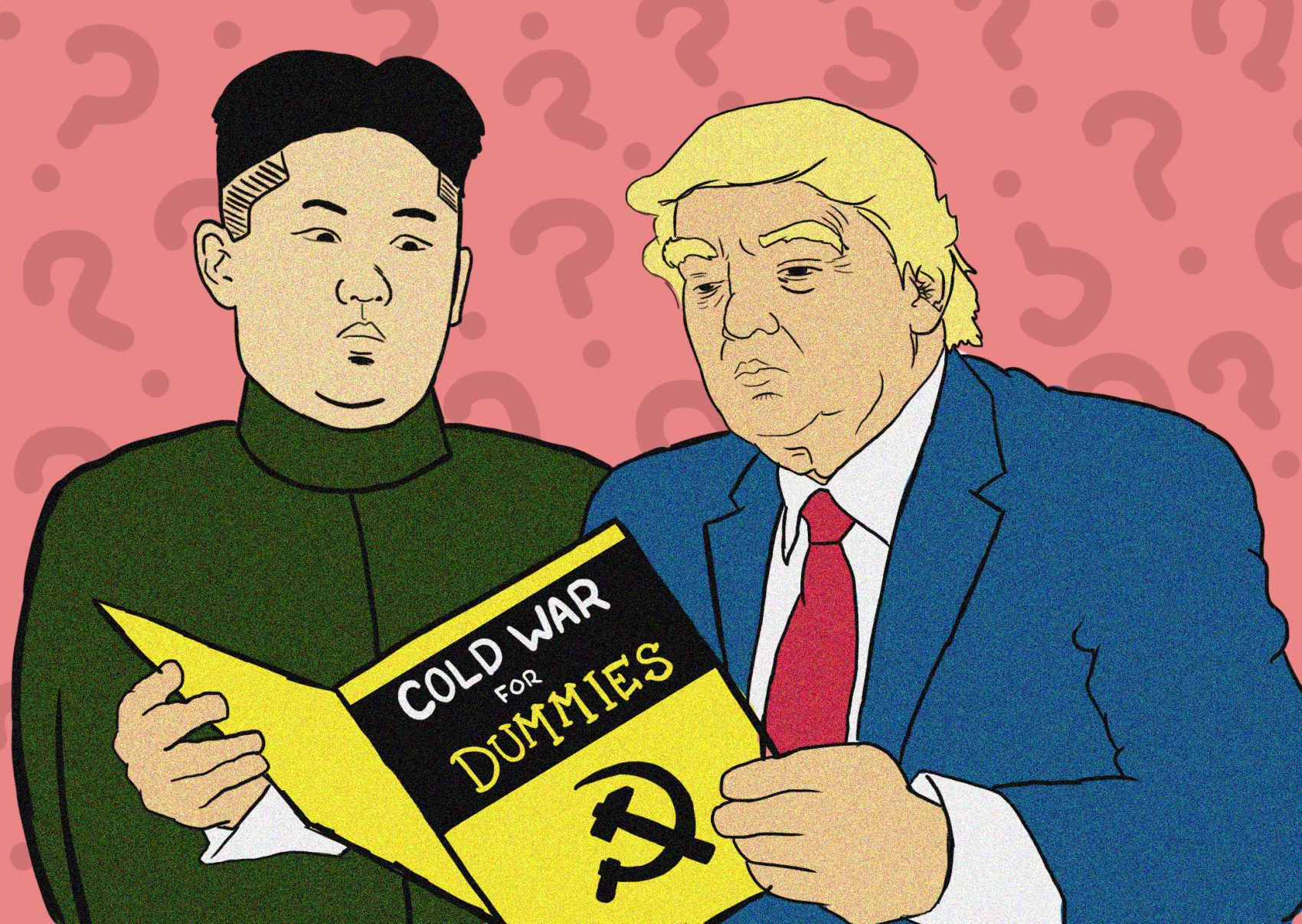

Whether it’s over a period of centuries, decades or days, history always seems to have a way of repeating itself. This time, it looks like the constant threat of nuclear annihilation is coming back, like it did in the Cold War.

In case you missed it, the Cold War was a period of tension between the United States, the Soviet Union, and their allies post-World War II. The issue at hand was largely about power– both wanting to be the world’s largest superpower at a time when world politics, and much of Europe’s landscape, had been muddled by the destruction in the wake of World War II.

The war ended in 1945, after the USA made it abundantly clear they had nuclear weapons. The US destroyed two of Japan’s major cities, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, with atomic bombs to force Japan into surrender. The USSR realised these bombs were a way to climb the world political ladder, and set out to create and stockpile nuclear weapons.

The war was labelled ‘cold’ due to the mainly verbal nature of the conflict – ‘hot’ conflicts like the ones in Korea and Vietnam did flare up, but the US and USSR mainly threatened each other with their nuclear capacity. The world knew that ‘mutually assured destruction’ was one of the few safeguards in place – if one country launched their nuclear weapons, retaliation would be immediate, leaving both decimated.

The last year has seen escalating nuclear weapons-related tensions between the USA and North Korea, particularly after Donald Trump’s rise to power. Their war is one of words too, with Trump recently tweeting that “I too have a Nuclear Button, but it is a much bigger & more powerful one than his” in response to Kim Jong-Un’s statement that a nuclear launch button is “on his desk at all times”.

Their fighting words align with some of the themes of the Cold War period: a democracy versus a communist regime, and two countries threatening to use their nuclear stockpile to show their power.

Dr Iain Henry, a lecturer at the Strategic Defence and Studies Centre at the Australian National University says that while North Korea is a threat, it cannot match the power held by the Cold War-era Soviet Union.

Dr Henry said that while North Korea does have a nuclear weapons program, “it is nowhere near as powerful as the Soviet Union was during the Cold War. North Korea has no economic clout or ideological appeal beyond its own borders. It does have a very large army, but that doesn’t mean much if you don’t have more sophisticated capabilities to support them in wartime.”

While Dr Henry sees some parallels between current tensions and the Cold War, he is confident the idea of mutually assured destruction will continue to act as a safeguard, stating “the primary role of nuclear weapons is not their destructive potential on the battlefield, but having them linger as a threat in the background to prevent escalation past a particular point.”

One main concern Dr Henry has focused on is technological: some of the most dangerous moments of the Cold War were when early warning radars mistakenly reported that the other side had already launched a nuclear attack. While Cold War radar operators waited for confirmation of attack, there is concern North Korean military personnel may just fire immediately.

Another is American attempts to coerce North Korea into negotiations could be misread – military exercises on the Korean Peninsula, for example. While America might be posturing its military might to encourage North Korea to negotiate, Kim Jong-un may see it as a sign of imminent attack.

“Washington might think that they are sending a very clear message: ‘negotiate, or else’. But there is a risk that Pyongyang won’t receive that message clearly, and might conclude that they are about to be invaded.”

“If North Korea believes this, they will have a significant incentive to use their nuclear weapons before they are destroyed.”

Overall, Dr Henry is cautiously optimistic. While it is terrifying Donald Trump has access to America’s nuclear codes, he hopes America’s allies will be successful in dissuading Washington from a pre-emptive attack.

At the end of the day, it doesn’t look like this is going to be another Cold War by any stretch. While the war of words between two leaders continues, it is unlikely to escalate to a nuclear level, for fear of the devastation these weapons will cause.