By Alexandra Middleton | @alexandramidd16

Photo by: Pixabay

‘When I say the word bitch, what comes to mind?’

Amanda Montell asks this question in the opening sentence of her first book Wordslut. This ‘feminist guide to reclaiming the English language’ proffers a witty insight into how language shapes us. Montell further explores the links between language, gender and power, urging women to embrace their unique relationship with the English language.

According to Montell, when the word ‘bitch’ originated some 800 years ago, it had nothing to do with a woman (or a dog), as many would ostensibly think; it was merely used to reference a person’s genitalia. Montell goes on to contend that the somewhat contentious term ‘slut’ was never intended as having sexual connotations; it was once used to describe an untidy woman or man, before evolving overtime to be associated with promiscuity and prostitution.

These crude terms are among the various gendered insults Montell deconstructs throughout her novel, offering readers a history lesson into the evolution of language and how it is used to gaslight women. Montell asks us to approach language usage and gendered insults in a way that doesn’t perpetuate ‘toxic gender stereotypes’. Wordslut shines a light on the intricacies of words, grammar and speech, further breaking down how language directly correlates with the patriarchal nature of society.

Montell demands we ‘verbally smash the patriarchy’, highlighting how the reclamation of gendered insults is a form of activism. Take the example of the word ‘suffragette’, which was a term originally used to diminish or smear women’s liberation activists; ‘suffragettes were husbandless hags who dared to want to vote’. Feminists reclaimed the word during the women’s liberation movement and used it as their own slogan; it is now recognised as having positive associations with women’s voting rights and freedoms, and feminism.

As a self proclaimed feminist and ironically self titled ‘wordslut’, Montell insists that ‘it’s high time the subject of gender and words makes its way beyond academia and into the rest of our everyday conversations’. Montell breaks down linguistics and sociology in terms easy enough for us to understand, defining linguistics as ‘the scientific study of how language works in the real world’. She then goes on to explain how ‘the study of language and human sociology intersect’, further divulging how people use language to express gender. Research and fascinating interviews with renowned linguists such as Lal Zimman, Deborah Cameron and Sonja Lanehart throughout the novel demonstrate Montell’s knowledge and passion for linguistics and feminism.

Montell’s tone throughout her novel is casual whilst her style of writing is sophisticated. The combined use of millennial language, swear words, and hilarious personal anecdotes make for an entertaining, relatable and thought-provoking read. The novel is broken up into twelve chapters, each covering different topics in relation to gender, feminism and language. Montell crafts a captivating and well written prose, making it easy and enjoyable for the reader to digest this strong serving of feminism. Wordslut dissects a range of more serious societal issues, including sexism, homophobia and misogyny, whilst leaving ample opportunity for humour, jokes and comedic irony.

After defining sociolinguistics and breaking down our love-hate relationship with gendered insults such as ‘skank’ and ‘hoe’, Montell delves into the complex issues of gender, sex and what it means to be a woman, as well as the role language plays in all of this. The novel then explores the concept of women’s speech and conversation ‘when dudes aren’t around’, before refuting the notion women ruined the English language, instead insisting ‘they, like, invented it’. Montell explains why we use the word ‘like’, justifies and applauds women swearing, and advocates for more women occupying positions of power. The terms ‘female doctor’, ‘woman president’ and ‘SHE-boss’ are called into question; why do we need to specify if a woman is a doctor, president or CEO when we don’t do the same for men? Why do we call inanimate objects like cars and boats ‘she’ (she’s a beauty!)?’ Montell examines why male is the default, not merely in English but in countless languages across the world, like Spanish or French, in which gender is heavily rooted, thereby forming preconceived notions that certain roles are inherently feminine or masculine.

Montell also references the seriousness of sexual harassment and assault, dedicating an entire chapter to confusing cat-callers. She explains why women, especially those in power, are sexualised or condemned for the way they speak, giving the stark examples of Hilary Clinton and Scarlett Johansson. Women cannot allow the patriarchy to envelop them, thus Montell proffers a guide for women to stand up for themselves and ‘verbally smash the patriarchy’.

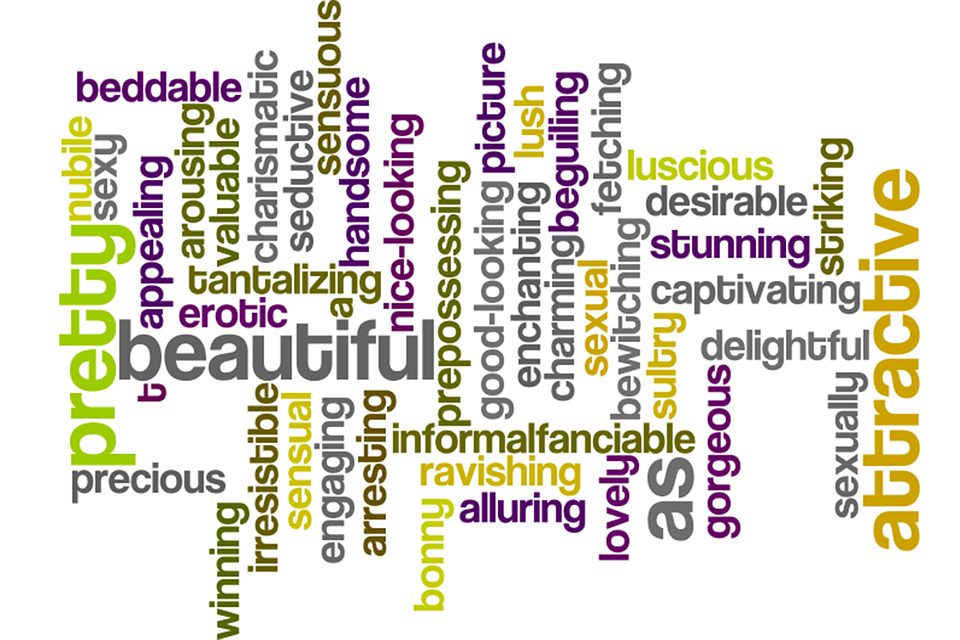

Wordslut teaches readers an empowering English lesson. An approachable, inspiring and above all, faultless read, the novel provides an exceptional understanding of why we use words, further explaining why women should embrace and take ownership of language. Montell’s underlying feminist message is that of equality and autonomy through the power of linguistics, reminding us that ‘pretty much every corner of language is touched by gender’.