By Sean Mortell

Fists are clenched.

It’s April 16, 2016. Loud voices erupt from the Windy Mile, a popular pub in the north-eastern suburb of Diamond Creek. A Saturday night crowd spills onto the street. Alcohol-infused tension boils over.

A 33-year-old man watches the fight unfolding between men and boys. He’s seen it bubbling. He makes the decision to join. A young man with long brunette hair rushes towards the brawl. His name is Pat, and he’s always helped his mates. He’s what you’d call a good friend.

Pat makes the decision to help. He seizes a friend from behind. His muscles tense. They’re exhausted after a game of senior footy during the day. Yanking his mate from the aggressor, the young men assume the confrontation has lost its sizzle. But a wild arm swings. In a horrific arc of futile anger, pulsing knuckles connect with the back of the long-haired helper’s head. Pat is rocked by the impact. He carries on pulling his mate away. Little does he know that blow will end his life.

Pat Cronin’s death epitomises the trauma caused by one-punch attacks. His family’s reaction constituted shock. It was a moment “you never think is going to happen to one of your own”. Pat’s father, Matt Cronin, powerfully objects to the label ‘one-punch’.

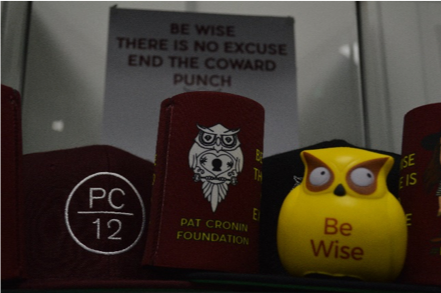

“I call it a coward punch, giving it a negative connotation compared to one-punch. Who wants to be known as a coward?” Matt says. His eyes carry the weight of mental fortitude. He absent-mindedly fiddles with a dark red band that adorns his wrist. The faded yellow lettering reads ‘Be Wise – End the Coward Punch – PC12’.

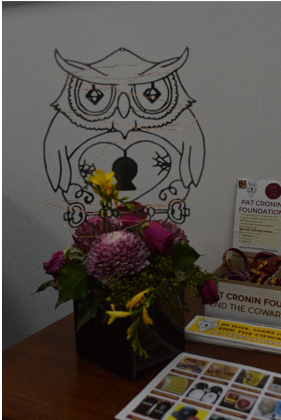

To the surrounding community, Pat is known for his long hair and footy jumper. His cartoon depiction is emblazoned across the Pat Cronin Foundation, along with the ‘Be Wise’ owl which he drew before his untimely demise. His death has inspired his family to act against coward attacks and start the Foundation.

“A day after Pat’s death, we had an open house for family and friends,” Matt reflects. “I was standing on the veranda out the back of the house when some mates asked what they could do to help. We had a house full of flowers, but they understood flowers don’t achieve a lot.”

Matt and the Cronin’s moved swiftly after the tragedy. On April 18th Pat was removed from life support after being declared brain-dead the day before. By June 2016 they were a registered charity. The dissemination of education against the coward punch had begun.

It couldn’t have happened to a less-deserving family.

By self-admission, they have “always been very community-minded people”. Both Matt and his wife Robin have been heavily involved with Research Junior Football Club and the connected Lower Plenty Football Club. They’ve been on committees. Matt has become a life member at Research. Now, their wonderful work is dedicated to honouring Pat.

“For us it always comes back to honour,” Matt states. “Everything Pat did that night was honourable, so it makes sense to honour him. We want his memory to live on as someone who will be remembered not just for his long hair and footy jumper but also as a good person.”

Throughout the north-eastern suburbs of Melbourne, the dark red wristbands are becoming more prominent. Taking over from other anti-violence groups such as ‘Step Back Think’ and ‘Stop. One Punch Can Kill’, the Pat Cronin Foundation is now at the forefront of coward punch awareness. The foundation stems from the values of respect, education and awareness.

Matt and his family have also embarked on a personal mission for law reform on the coward punch. So far, their judicial journey has been an arduous one.

Andrew Lee, Pat’s killer, has shown “no signs of remorse” for his actions. His minimum period in jail could be as little as five years. But this heartache hasn’t slowed Matt and his work with the foundation.

Matt and his grieving family have had to take on another mission. Alongside educating Victorians about the heart-shattering outcomes of coward punches, they have been advocating for law reform. Research is a private pillar for the Cronin’s.

“I want people to understand the law stuff is privately done, like a Cronin family mission,” Matt says. “We have to make it easier for judges to use the coward punch provisions.”

Their work has been influential in the space. The recent introduction of the ‘coward punch law’ means people found guilty must serve at least 10 years in jail before becoming eligible for parole. Now they have to work with the legal system to ensure this law is implemented.

But the Cronin’s also have to come to peace with what happened to their beloved Pat. They’ll never experience a feeling like closure. They have been subjected to their own life sentence for raising a young man who “grew up knowing to pull your mate out of trouble”. Matt’s resilience is steely. The family deserve a break from this torment.

That’s why they are currently in Italy, soaking up the beautiful sunshine of summer in Europe. But it’s not a normal family holiday.

“Part of the reason for this holiday is Pat. He went on a trip with Whitefriars College to Italy for three weeks in Year 11,” Matt explains.

The host family he stayed with remember the long-haired boy. His smile. His 17thbirthday party was held in the host village. The community was shocked and devastated to hear what had happened to the boy they had accommodated. Pat’s spirit had captured them.

The journey is perhaps less for holiday purposes and more for soul searching. He knows it’ll be sad “but just had a feeling” that the family had to make this trip. It’s not necessarily for themselves, it’s about the Italian community that is hurting.

When the Cronin’s arrive back home, the foundation and their work will recommence at full-bore.

“We’ll continue to research. One major factor we know is that alcohol plays a massive part in coward punch attacks. Now we just need to spread the message of being wise,” Matt says.

Matt believes his family will find a way to enjoy their mission to Italy. The Cronin’s are what you’d call troopers. They’ll take their kindness to Europe then channel it into hard work once they return home.

“We’ve taught our kids to pull your socks up and have a go. It’s very easy to just sit in the corner and cry. It doesn’t do any good for us, our kids or for Pat,” Matt explains with an air of defiance.

Matt smiles sadly. His eyes show his yearning for his son. He details how he’ll see Pat again in the afterlife, but it’s just “not our time yet”. Until then, the Cronin family have had an internal fire stoked that means they will give their very best to honour Pat. And to help others. Matt doesn’t want to share a torturous bond with other devastated families.

While Matt passionately discusses the work he will continue to do in his son’s honour, emotion shrouds the board room we sit in. The atmosphere becomes lighter. You can feel Pat in the room. Looking down at his dad. Smiling once again. Proud.