I was finally doing something that really mattered. Sleep felt productive. Something was getting sorted out. I knew in my heart—this was, perhaps, the only thing my heart knew back then—that when I’d slept enough, I’d be okay. I’d be renewed, reborn. I would be a whole new person, every one of my cells regenerated enough times that the old cells were just distant, foggy memories. My past life would be but a dream, and I could start over without regrets, bolstered by the bliss and serenity that I would have accumulated in my year of rest and relaxation.

I’ll disclaim this: if you’re looking for a book with wholesome, pleasant, and likeable characters–Ottessa Moshfegh is not for you. This contemporary American writer has received criticism for her provocative plots, grotesque imagery, and a slew of unlikeable characters. In fact, her third novel almost challenges the threshold of just how unlikeable her characters can be. The writing is sardonic, it is savage, and it is quintessentially Ottessa Moshfegh.

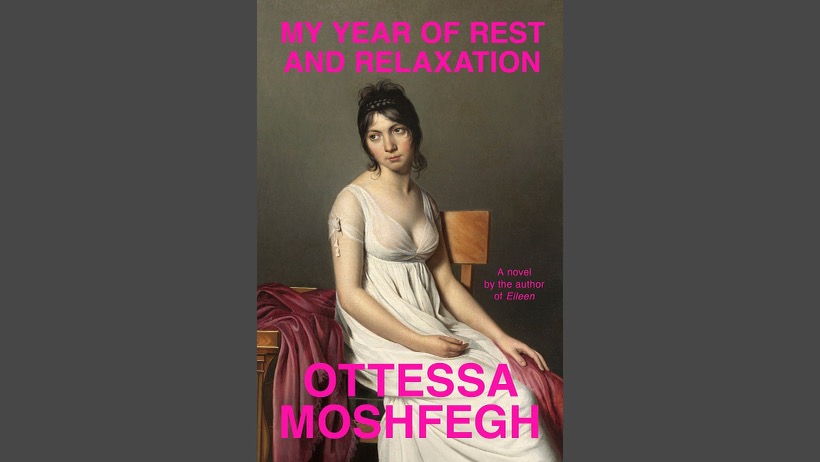

In short, Moshfegh’s third novel, My Year Of Rest And Relaxation follows an unnamed narrator, a twenty-something Columbia art history graduate living in the Upper East Side of Manhattan, paid for by her inheritance. She’s pretty, thin, and blonde, working as a receptionist at an art gallery where subversive art is just “canned counter-culture crap”. But the latter advantages comically function as a facade to conceal what lies beneath; a character suffering from the ennui of her own privilege, is perpetually misanthropic and as a result, can barely stand her own consciousness. Her solution? To embark on a year-long chemically induced sleep enabled by prescription psychopharmaceuticals: “My Ambien, my Rozerem, my Ativan, my Xanax, my trazodone, my lithium. Seroquel, Lunesta. Valium.” (Most of which are made-up drugs). Her medication is prescribed by Dr Tuttle, a Yellow Pages quack doctor who wears a neck brace and a white sleeveless nightgown into her office, which is ripe with the smell of cat piss. With the help of this cartoon psychiatrist, the protagonist believes that after a year of pharmaceutical hibernation, she will be reborn as a new person, ready to re-enter the very world that she desperately desires to detach herself from.

So, what is it that she is trying to remove herself from? As aforementioned, this book has a myriad of unlikeable characters, even more so through the eyes of our uncongenial protagonist. Her nihilistic fog emerges following the death of her parents with whom she had a distasteful relationship–and spends a lot of the book recalling it as such. Her dad, a disparaging college professor and her mum, a vain alcoholic, who expressed impatience and irritation during her own husband’s funeral through a symphony of “sighs and throat clearings”. Her best friend Reva is a size 4, self-made corporate who annoyingly preaches off the advice from self-help books whilst being endlessly jealous of everything the narrator has–and loves being vocal about it too. Her only two male companions consist of her asshole Wall-Street ex-boyfriend Trevor, with whom she has a toxic, abusive relationship, and Ping Xi, a modern artist of said “canned counter-culture crap” and an ambiguous love interest.

Moshfegh writes amidst the backdrop of pre-9/11 New York, a time where everyone has seemingly care-free lives, plagued with an absurd optimism. Perhaps Reva and the narrator’s contrasting attitudes show two paths of coping with unhappiness: one of shallow, delusional positivity and the other of apathy and succumbence to inactivity. Our protagonist delights in her isolation and her avoidance of the problems of other people: “This was the beauty of sleep — reality detached itself and appeared in my mind as casually as a movie or a dream. It was easy to ignore things that didn’t concern me.” She finds any sliver of drive from pills, VHS tapes because they turn “everything, even hatred, even love, into fluff I could bat away. And that was exactly what I wanted–my emotions passing like headlights that shine softly through a window, sweep past me, illuminate something vaguely familiar, then fade and leave me in the dark again.”

This philosophy speaks to a universal (and privileged!) exhaustion. Don’t we all harbour the desire to remove ourselves from the world from time to time? To eschew the worries of money, maintaining a job, socialising with friends and family? So, to an extent, you can empathise with the narrator’s monotonous life and the lethargy that comes with it–not to mention the pointlessness of it all. Although this novel is set two decades ago, there is also something about it that speaks to the hyper-contemporary ideas of ‘wellness’ which permeate social media today. And of course, it is amusing to have personally picked up this book now under a climate where isolation is not a personal choice, but an actual necessity enforced by law. These past couple of years have been our year of rest and relaxation–or rather, our year of anxiety and laziness (but maybe that’s just me).

What also interested me was how this book was received by audiences online, particularly young girls. Many have instead applied a lens of admiration towards the narrator’s beauty and affluence, romanticizing her WASP status. While it’s apparent that there has been a comeback of post-feminist contemporary culture amongst online communities, it is amusing to see such an interpretation of the novel; a story about the emotional and temporal dissatisfaction that comes with the indulgence of materialistic mores.

One of the pleasures of reading Moshfegh is the blatant sardonicism that imbues her writing. She does not shy away from the murky parts of life that we tend to gloss over, nor does she shun away from being down-right offensive, dark and obnoxious–especially when it comes to class and privilege. In a 2015 interview with VICE Moshfegh describes the affection people have on her writing:

My writing lets people scrape up against their own depravity, but at the same time it’s very refined—the depth of it hides behind its sophistication. It’s like seeing Kate Moss take a shit. People love that kind of stuff.

This was my encounter with Moshfegh’s work and I am eager to read the rest of her oeuvre. My Year Of Rest And Relaxation is definitely not everyone’s cup of tea. But despite its repetition, a lack of plot, the narrator’s interminable stream of thoughts (a lot of which are ridiculously vile), and an inherently hateable protagonist (which is the point!) it was without a shadow of a doubt, an entertaining read. While some readers champion her as feminist hero, others frame the narrator as a savage satire of privileged white women–I guess it is up to you to decide which.

Review written by Beatrice Madamba