Content warning: This page contains information related to abuse that readers may find confronting or distressing.

Last Summer is French director Catherine Breillat’s latest film; it is sun-drenched, steamy and an undeniably difficult watch. This film is not light-hearted and audiences who might have experienced sexual violence or grooming should tread carefully before watching it.

The initial premise of the show positions it similarly to recent films such as Luca Guadagnino’s Call Me By Your Name and Richard LaGravenese’s A Family Affair via the common trope of an older woman falling for a younger man. There is a stark difference in the way Breillat tackles this theme in Last Summer through a much more direct and critical lens of relationships taking advantage of children and young people.

Unlike the aforementioned films, the target audience of Last Summer is also unclear in a similar vein to It Ends With Us. On one hand, the Australian classification is MA15+, however, the lewd scenes can feel like audiences are being blindsided by crass depictions of sex.

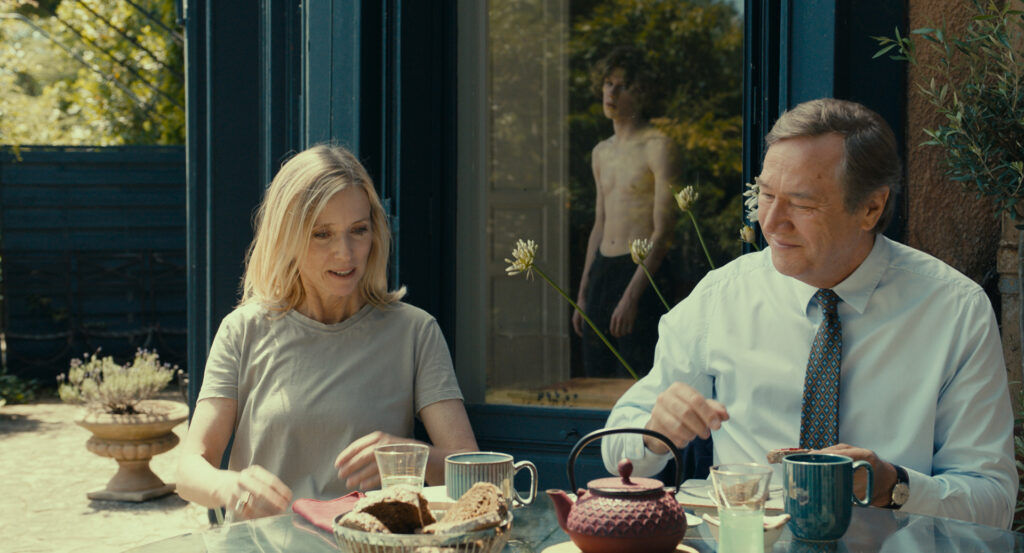

There are three main characters who act as central pillars in Last Summer. Anne (Léa Drucker) is a renowned attorney specialising in cases involving misconduct of children, Pierre (Oliver Rabourdin) is Anne’s husband and Theo (Samuel Kircher) is Pierre’s 17-year-old son from another relationship.

From the outset, Anne and Pierre’s relationship is depicted as being relatively strong with a sense of understanding that they’re both growing older, and life has weathered their bond. There is a foreboding sense of looming tension as Anne recalls a frivolous crush she had as a young teenager on a much older man.

This disclosure foreshadows the relationship Anne and Theo will engage in when he moves into the family home.

Upon first introduction, Theo comes across as a tough kid with that typical teenage angst; he’s poised ready to fire back with attitude when asked to do anything he doesn’t want to do and he’s unafraid of authority. This is an important piece of context that shifts as the film progresses.

The first half of the film in essence delves into the ways blended families coexist in a household. This also establishes the context for Anne and Theo’s relationship and the preparatory phase of grooming.

It isn’t until roughly half-way through the film that the tension between Theo and Anne is broken via an uncomfortably dramatic, wet and sloppy kiss, a symbol of the gap in life experience between both characters.

As their bond seemingly deepens and moves into an intense sexual affair, it becomes clear that Theo’s attitude that might have easily been misconstrued as merely ‘f*ck boy’ behaviour is a cover for his emotional and sensitive heart. This added layer of boyishness creates a stark difference between his character and Anne, who is clean-cut, put together and well regarded in high society.

There are numerous intercourse scenes between Theo and Anne throughout the film, but the extent of their sexual relationship is driven home through markers that there is more happening that isn’t explicitly shown to the audience.

Throughout this film, Breillat isn’t condoning abuse or justifying the affair, she’s taking a stance and creating dialogue around the ways some women groom and abuse children and get away with it.

There is an irony in the dichotomy created throughout the film as Anne continues her work as an attorney while actively engaging in a relationship with her 17-year-old stepson.

The film comes to a head when their affair is uncovered by Anne’s sister at a family party. The audience later sees Theo start to unravel as the reality of the situation sinks in.

When Theo consults legal advice, Anne leverages her position of power and makes it clear that no one will believe him because there is no hard evidence, and it is her word against his.

This blatant dialogue around grooming, particularly in cases where it is a woman who is the groomer is uncomfortable but a necessary conversation in a contemporary context.

The film ends with Theo visiting Anne is a clearly vulnerable state following an extensive legal ordeal and once again engaging in sexual activities which drives home the internalisation of abuse that groomed children can feel and the distorted mindset and perceptions of conduct.

While the film is set in France, when looking at grooming and sexual violence in Australia, the Australia Bureau of Statistics reported in the Statistics of personal safety that 5 per cent of men reporting being sexually abused before the age of 15. Further, in a Birth Cohort Study, 19.3 per cent of males self-reported child sexual abuse at age 21.

These statistics are a reminder of why films like Last Summer are so important in creating conversations on a global scale but should be viewed carefully by vulnerable audiences.

This film will be available to view at select cinemas on September 5.

If the contents of this article have brought anything up for you, help is available. Lifeline: 13 11 14

Eheadspace

1800 RESPECT: 1800 737 732

RMIT Support Services

By Louis Harrison

Header Image via Potential Films