The first thing we were taught in our Introduction to Journalism lecture was: don’t fuck the source. One of the second things we were taught was: learn shorthand.

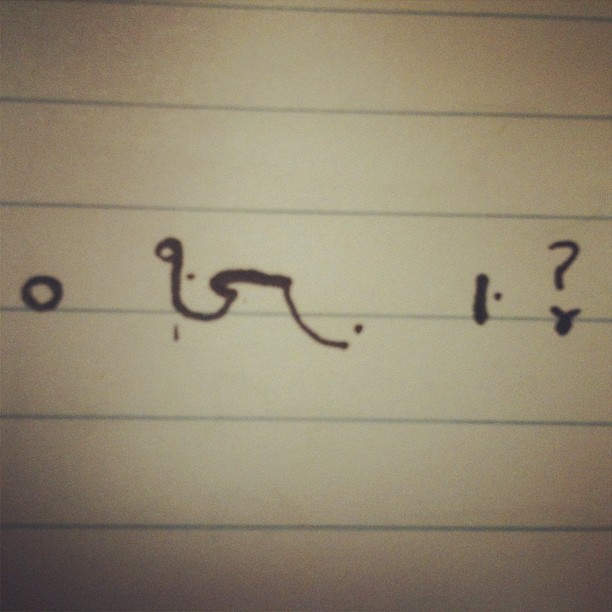

In case you were wondering, stenography is the art of speed-writing. This is usually achieved by scribbling down notes of an interview or speech in shorthand. To the naked eye, shorthand looks like nothing more than a series of indecipherable scribbles and dots. To the stenographer, though, these scribbles and dots can be transcribed into words (and, in some instances, entire phrases).

The obvious question is: ‘Why would you go to all that effort to learn shorthand?’ Well, the truth is that grasping shorthand takes a lot of work. It’s like learning another language, or a musical instrument. It takes a lot of time and practise. I did a night course through Swinburne University last year (which is no longer running due to the TAFE cuts) and each Thursday night I would get home absolutely exhausted, my mind buzzing with hooks and circles and pesky –ster loops.

But the hard work does pay off. Imagine being able to write The dog went to the market in the same time that it would take you to write The dog in longhand. The average person writes at a speed of around 20 to 30 words per minute, but in shorthand speeds of up to 160 words a minute or more are achievable. (By comparison, the average person speaks at around 140 words per minute.)

While I can only write shorthand at around 80 words a minute at the best of times, it’s definitely a valuable skill to have and I’m glad I took the time to learn Pitman 2000 (Pitman and Teeline are the two main types of shorthand—Pitman is phonetic and therefore faster but harder to learn, whereas Teeline is based off spelling and therefore is slower but much easier to grasp).

People are still sceptical of shorthand, though. In an age of keyboards and screens stenography is widely viewed as a dead art. It’s considered more important to be able to edit and upload audiovisual content and have a basic grasp of

coding. When people find out that I know shorthand, they often roll their eyes and tell me to just use a dictaphone. The truth is that people who say this have clearly never had to transcribe or listen to a 60 minute interview simply to find the right quote. Besides, I often record my interviews where appropriate and where the interviewee feels comfortable—both recording and note-taking seem to work best. Journalism is all about immediacy, and reporters rarely have the time to sit down at a desk and play back an interview.

On the other hand, what if your dictaphone breaks? What if you didn’t press ‘record’ like you thought you did? I know of plenty of skilled journalists who have had these problems. You’re not allowed to take a recording device into a court room, and I have interviewed people who have simply refused to have their words recorded. There is nothing more embarrassing than having to ask the interviewee to slow down as you struggle to write down what they say, your forehead slicked with sweat and your hand numb from so much writing (this happened to me when I was interviewing a particularly nasty women when I was 18). Or, for that matter, calling up your interviewee again and asking them if they can redo the interview because you screwed up big time.

With this in mind it is no surprise that Fairfax and News Limited cadets all learn shorthand as part of their training (alongside obvious areas such as media law and ethics). I’m not sure where you can study shorthand now that Swinburne doesn’t offer it anymore, but I would encourage every journalism student to give it a go. After all, our industry is a competitive one. This doesn’t mean ignoring other skills important to this day and age—but it does mean you’ll be able to write secret notes to your special someone.

Hashtag is a weekly blog by Broede Carmody. It covers journalism, student media, current affairs and publishing. He would appreciate it if you didn’t sue him. Instead, follow him on Twitter via @BroedeCarmody.