Harley Davidson’s are not, as far as serious motorheads are concerned, very good bikes. As one writer put it, Harley Davidson offers the “best, most-refined 1940s technology around”, and some have refered to them as an inefficient relic of a bygone era. The bikes have improved since the 1940s, but much of the actual product seems still to be more nostalgic than anything else. It’s heavy, it’s bulky, it’s noisy. In it’s early days, the constant threat of streamlined Japanese imports nearly pushed the company into bankruptcy, twice.

How then did Harley Davidson become such a valuable company, estimated to be worth almost $7.7 billion? It is a story of, more than anything else, branding.

Branding in its most literal sense is the use of symbol to separate one product from the next. A brand, initially, was used to mark cows so that farmers could easily spot their own cattle. It’s no surprise then, that the word itself is derived from an Old Norse word meaning “to burn”.

When brands were first used to distinguish products, they too were almost as simple as the branding of a cow. During the industrial revolution, a sudden influx of mass products became available and they needed a wider audience. Consumers, however, were used to buying local products. Brands were used to make products seem trustworthy. Some of the earliest brands included Campbell soup and Coca-Cola.

In modern times, brands have become more important than ever. With an infinite variety of products and advertising messages hurled at consumers every moment of the day, distinction beyond the actual product is essential. There are many similar products in every category, and as Vance Packard put it in his book The Hidden Persuaders, “the greater the similarity between products, the less part reason really plays in brand selection.”

What’s more, consumers are affluent, with base needs overly satisfied. To get us to buy more and more products that we rationally don’t need, advertisers must convince us that products can meet more intangible, emotional needs.

The successful modern brand is an emotional one. It is now widely accepted by scientists that emotion is more powerful than reason, particularly in consumer decision making. Kevin Roberts, the CEO of Saatchi & Saatchi, said in 2002 that “we now accept that human beings are powered by emotion, not by reason. Emotion and reason are intertwined, but when they conflict – emotion wins every time.”

A brand is about using emotion to go above and beyond a consumer’s rational response to a brand, in bind to consumer to a product in a lasting way. A brand adds value – intangible value – that is more than the difference between the actual product value and the selling price. Brands offer us community, meaning, and an identity that we connect. When we purchase a branded product we buy into that identity and, through association, become it.

But Roberts also argues that the modern term brand has become overused. We have lost touch with what should be at the core of any great brand: the consumer’s relationship with it.

And so Roberts proposes the lovemark. What is a lovemark? A lovemark is a way of inspiring loyalty without reason. A lovemark brand dissolves all competitors to create for themselves a “category-of-one”. The lovemark brand develops such a strong, lasting relationship with consumers that it is akin to, yes, love.

And Roberts, ever the advertising man, has been so ambition as to breakdown, quantify, and measure what exactly brand love consists of.

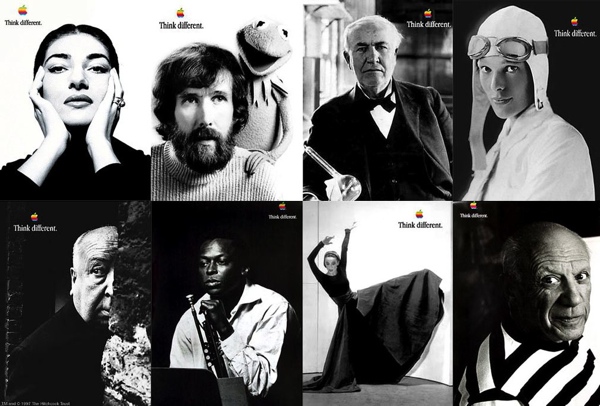

A lovemark brand must create, in equal parts, mystery, intimacy and sensuality. Mystery is created through story telling, stringing together the past present and future, taping into our dreams, our cultural myths, our icons. Apple is brilliant at this. When you buy an Apple computer, you are buying into the idea of being creative, being innovative, being a forward thinker. You wish to be someone who, as the ad puts it, who “thinks different”.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nmwXdGm89Tk

Intimacy with brand means making the brand feel like a good friend who will never let you down. The irony is that millions of other people are having that same experience of intimacy. Sensuality is about evoking the senses and thus making consumers feel connected to the product. Apple again, is a very tactile experience; from the feel of the keys, to the recognizable click of your iPhone opening.

Apple is a lovemark brand. So is Harley Davidson. It too has sensuality down pat, you’re literally sitting on the product. And that distinctive grumble is no accident. It’s the result of putting a large engine in a small space, causing the cylinders to fire unevenly and create that chop chop choppy sound.

Harley Davidson has tapped into it's consumers desire for freedom, rugged individualism, and rebellion. It is about feeling like a rebel, even when you aren’t one. In fact, your average Harley Davidson rider is increasingly white-collar baby boomers – far from the companies Hell’s Angels origins.

Interestingly, Harley Davidson has spends very little money on advertising. Last year just 15 per cent of money was spent on tradition media. They believe instead, in the power of word of mouth. The consumers, because they love the bike so much, spread the love. The defend, they gush. They get tattoos, literally branding the identity of Harley into their skin. All employees are also hardcore fans and go out for rides with their customers. They hold huge biking events, like a recent party in Rome.

As is the case with Harley Davidson, Roberts adds that true lovemark brands are often born naturally within culture, rather than being constructed outside culture and thrust into it. Advertising can spread the love, and even strengthen it. But part of that love must be natural and real within the consumer. The kind of love, perhaps, that exists between a man and his motorbike.

Beth Gibson