By Gus McCubbing | @gusmccubbing

Image sourced from https://pixabay.com/

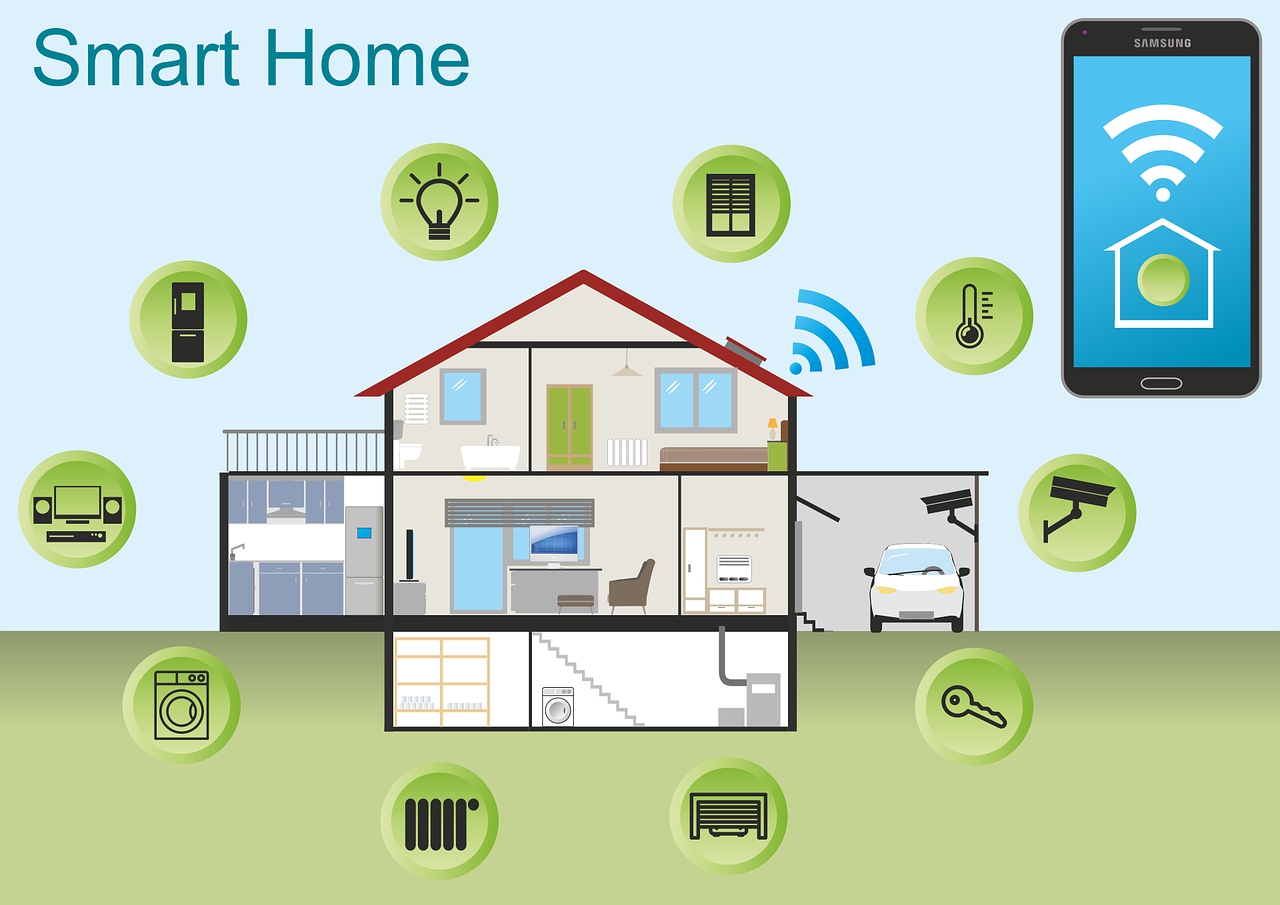

Smart home technology, which has officially arrived in Australia, may well change the way we live.

Essentially, this technology allows household electronics to become interconnected, enabling users to do things like automate their lights and pre-heat or cool their rooms before coming home from work – all through their smartphone.

Beyond the promotion of these convenient lifestyle features, smart home technology is also being marketed as a way to improve energy efficiency and cut power bills.

However, RMIT University’s Dr Yolande Strengers and Dr Larissa Nicholls claim smart home devices may actually be doing the opposite.

“We think some of the lifestyle improvements that are being advocated – like better comfort, better security – they actually have an energy impact. They could actually increase energy consumption, as well as decrease it,” Dr Strengers said.

Dr Strengers acknowledges smart home technology has the potential to decrease energy usage by doings things like automatically switching off lights – which has gained attention from the energy sector – but she warns these benefits can be misleading.

“The energy sector in Australia are interested in smart home technology to help improve people’s energy demands in their homes, to lower energy bills, and to shift energy demands to other times of the day, for example when we have high demand on the network,” she said.

“[But] the smart home industry and their objectives for lifestyle benefits weren’t necessarily aligned with the energy sector’s interest in trying to help people save energy.”

The main demographic interested in buying and using smart home technology, Dr Strengers said, are usually younger people – men in particular – who have experience with technology.

“We tend to find that people who have a computer background, or think of themselves as tech-savvy are the ones who are going out and buying smart home technologies, alongside things like digital voice assistants – Google Home and Amazon Alexa,” she said.

And as Dr Nicholls explains, entertainment features are the primary selling point for products like Google Home.

“It’s about having pre-set scenes for the home, which might be a combination of certain types of music, combined with certain colours and levels of lighting that are designed to create moods,” she said.

“They give potential buyers the idea that just by pressing a switch, you’ll be able to change the ambience and mood of the household and potentially imbue a positive mood through other activities in the home, say, when you’re doing menial things like washing up.

“So, it’s very much about offering a nice and happy escape from the troubles of the world.”

For example, Samuel Ludwig, 28, who uses Google Home to control the light settings in his bedroom, ask for his favourite albums to played, or watch Youtube clips on his TV, said his favourite aspect of the device is the control and ease it provides him.

“You have access to the internet via voice commands,” he said.

“You can get information on anything. On top of that, you can control any connected devices via voice commands.”

However, research published by Dr Strengers and Dr Nicholls last week has also shown many people outside the tech-savvy young male demographic found smart home technology either too complicated to use, or simply, pointless.

In their trial, Dr Strengers and Dr Nicholls gave 46 households off-the-shelf smart home devices which were promoted by stores like Bunnings and Harvey Norman as readily accessible for the mainstream population.

Given the volunteers were fully aware the trial would involve smart home technology, the results were very surprising for Dr Nicholls – one quarter of the volunteers didn’t even attempt to install devices, and another quarter couldn’t figure out how to use them.

“So, that presents an equity issue, because the energy industry is expecting households to use this sort of device to respond to future changes in electricity pricing,” Dr Nicholls said.

However, regardless of the fact their research suggests smart home technology won’t be the household energy saviour some are hoping for, Dr Strengers said these products look to have a strong future in the market among tech-savvy consumers.

“I think that we will see more and more people turning to them and becoming interested in them—they’re becoming more affordable, [and] they’re becoming less glitchy,” she said.

“A lot of people are still figuring out what they could use it for, and how they could bring it into their lives and incorporate it into something that will actually benefit them.

“But certainly in the homes that are embracing them, they are using them in a whole lot of varied and innovative ways that the designers probably didn’t even think about.”