Written by Molly Magennis

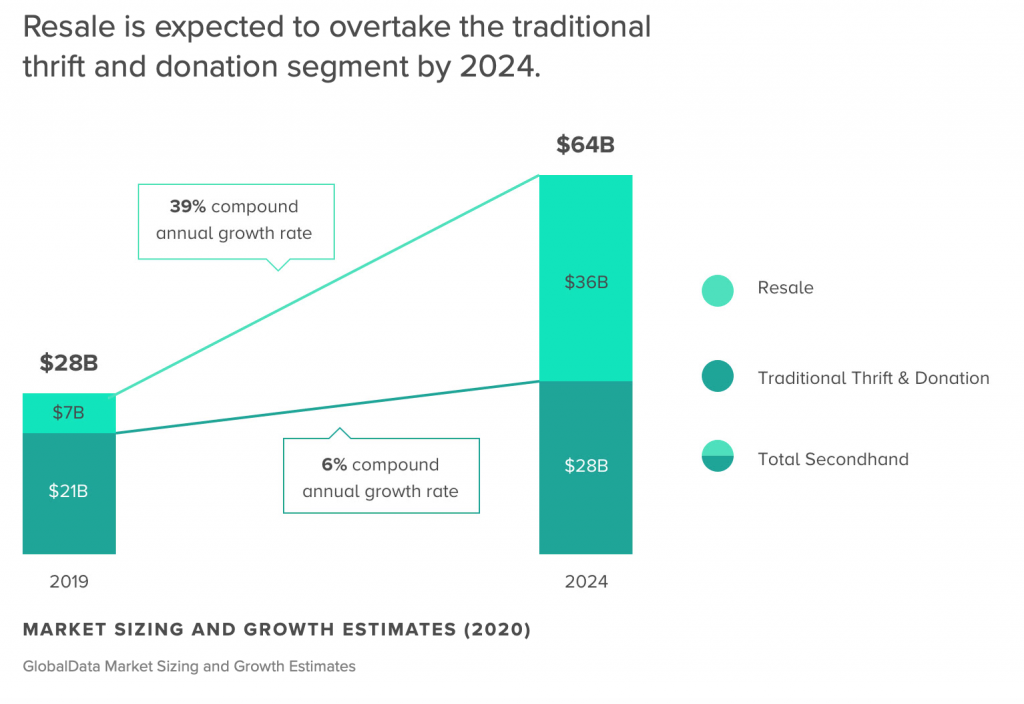

When online secondhand store ThredUp published their 2020 resale report, they stated the secondhand market was set to hit $64 billion in the next five years. They also reported the resale market was projected to grow two times the size of the fast fashion market by the year 2029.

According to the report, Gen Z’s are spearheading this secondhand/vintage movement with Millennials not far behind.

While this increase in popularity is a welcome sight for the ongoing sustainability push, it has also become a cause for concern, with many worried about the impact this increase might have on low-income earners who historically rely on op-shops.

The term ‘gentrification’ has been thrown around by many of those who hold such concerns. Simply, gentrification describes the process where a poor urban area is changed when affluent people move in. This improves housing and entices new businesses to come to the area, which in turn can lead to the displacement of the people who currently live in the area.

So, like a neighbourhood, the argument is that op-shops can become gentrified too. Common arguments as to why this may be occurring all relate back to the rise in popularity of vintage/secondhand clothing driven by Gen Z and Millennials.

While these concerns about how this may impact the underprivileged are valid, the question is, do these problems actually exist? Have Australian op-shops become gentrified?

Overconsumption

The first concern many holds is about the overconsumption of secondhand clothing. You don’t have to look far on social media to see how popular op-shopping (or thrifting as the Americans call it) has become. If you look up #thrift on TikTok, there are 2.4 billion views associated with that hashtag. Youtubers like Alexa Sunshine83 and Macy Eleni all frequently post videos which contain thrifting related content.

Much of this content is made up of ‘hauls’, where at the end of the video the influencer will show their audience a massive haul of clothes they have bought at an op-shop. This has perpetuated a sort of ‘haul culture’ where their audience (typically young affluent girls) also feel the need to buy excessive amounts of clothes they find at an op-shop, just because they can.

If so, many people are going into op-shops and buying huge, unnecessary amounts of clothes, what will be left for the low income, underprivileged people that actually need them?

This does seem like a valid concern. But according to Brunswick Salvation Army op-shop manager Elisa Peluso, we really don’t need to be worried about this. She says what people are missing out on, is that there are so many clothes being donated to op-shops every single day.

While there’s no doubt that the second hand market is rising, fast fashion continues to grow with the market currently worth $2 billion. Elisa emphasises that so many people are still donating serious amounts of clothes, particularly brand new ones.

“Regardless of whether our time of trend is wearing secondhand clothes, we still have the majority of our people buying brand new. Every single day. No matter what, there is a wealth there that buys brand new,” she said.

“What they do is wear it once. 50 percent of our items get in here and they’re still tagged.”

“I think the turnover in amount of items that come in through will always be enough. People just love to waste.”

Op-shops increasing prices on so called ‘trendy items’

The next major concern is because of this newfound popularity in secondhand clothes and the kind of people who now frequent secondhand stores, op-shops have jumped on this opportunity and are now increasing the price of their items. Particularly items with brands that they recognise to be of value to the younger population (Doc Marten, Levis and Harley Davidson for example). If op-shops are increasing the prices of their clothing, then this may make clothes inaccessible for the disadvantaged.

Elisa does admit that her store has increased their prices. However, this is not as straightforward as it might seem.

Elisa explains that the Salvation Army has just opened an online store, where they list their ‘higher ticketed’ items. She says that yes, while they are more expensive, the items listed on the website aren’t aimed at low-income earners who rely on op-shops, but rather the people who can actually afford to pay that much for an item of clothing (like Gen Z’s or millennials).

The money made on these products then just goes back into the system, giving the Salvation Army more money to spend on resources to help low-income earners.

“If you put it into perspective, you’ve got the people…that will buy those items for ‘x’ amount of dollars, but the welfare doesn’t care if they get Gorman or if they get Target. What they care about is [getting food] and putting the clothes on their back,” Elisa explained.

“Yes we’re still making the profit on their larger ticket items, but that money goes back into the Salvos independent areas, which looks after our welfare.”

“So if people like yourself or the hipsters want to come in and spend $60 on a Gorman vintage jacket or whatever, then so be it. I’m more than happy to sell it for that ticket price because I know where our money goes.”

The impact of upcycyclers and resellers

The final most common issue is kind of a combination of the two mentioned above. Online reselling apps and websites such as Depop and Poshmark are huge amongst the secondhand clothing community. It’s common practice for sellers to pay $5 for a t-shirt they found at an op-shop, and then resell it for $40 just because it’s ‘trendy’ at the moment.

Many argue that because of this op-shops have had to increase their own prices on all their items (whether it’s a ‘popular’ brand or not) to meet the demand. Again, this could price out the low-income shoppers in the area.

But Elisa says for op-shops like hers, this would never be an issue. Their main priority is always helping out those in need, no one would ever be turned away empty handed just because they couldn’t afford something.

“We would take care of all our lower income [earners] or welfare definitely. If something was high ticketed and they desperately needed a jacket or sneakers or whatever, we would look after them [as a] priority,” she said.

“We know the difference between a welfare client and a hipster. The thing is we do look after our welfare, that’s what we’re here and trained to do.”

“We’re not here to support our hipsters to look cool, we do make them look cool but it’s not the aim. We’re totally here to help our welfare and take care of our welfare first.”

All in all, it seems as though the only people resellers seem to be hurting are the people gullible enough to pay so much money for a ‘vintage’ Nike jumper.

Thankfully it appears as though op-shops are still able to do what they were originally created for – to help those in need. It’s actually thanks to the rise in popularity of secondhand clothing stores that they can continue to do this. So, for anyone that loves op-shopping and searching for vintage clothes, don’t worry, you can continue to do so guilt-free.