The cigarette. A little white stick used to inhale smoke into our lungs. It seems, in isolation from culture and health research, an object of desire. It does not shine like a diamond, nor does it make us giddy like a strong drink.

On the surface, it works through addiction: constantly and temporarily satiating the cravings it give us. But this alone does not explain its appeal. After all, why do we take it up in the first place, when our first, second, and third cigarettes are usually unpleasant experiences? Rather than physical addiction alone, it is the construction of a smoking identity that has turned the cigarette into one of the most potent, powerful symbols in modern culture.

Art, film and literature have all contributed to the power of smoking symbology. Actors like Humphrey Bogart gave smoking a masculine, life weary image. Film noir, with images of dimly-lit faces disappearing behind pools of smoke, added an air of mystery and melancholy to the cigarette.

Other actors, including Marlon Brando and James Dean, imbued the cigarette with the image of a young rebel. This idea of risk-taking and rebellion from one's parents and society has long attracted young people to smoking. (As a side: Lucky Strike capitalised on this with a 1963 ad pitched at college students. It read: “Lucky Strike Separates the Men From the Boys … But not From the Girls”. The irony was that young people were asserting their independence by becoming part of a mass consumer base of smokers.)

In art, smoking initially symbolised death, but came later to symbolise modernity, youth and nervous excitement. In literature, smoking is often used to evoke individuality and eccentricity, as is the case with Sherlock Holmes.

Another contribution to the collective smoking identity began during World War I. It was the first time in America when cigarettes were rationed to soldiers – they continued to be given cigarettes until 1975. This was, in reality, a huge promotional move by tobacco companies, sold to the government and soldiers as a way to boost morale. It provided, as one periodical wrote, the “last and only solace of the wounded,” and it emphasised the cigarette as an object of masculinity, strength and pessimism.

When Marlboro came onto the cigarette scene in 1924, many of these ideas behind smoking had already been established. Still, at that time, Marlboro was a woman’s cigarette. Many cigarette companies were being threatened by emerging negative health claims, and sought to counter these claims by releasing 'healthier' filter cigarettes. The common notion, however, was that there was something 'sissy' about filters.

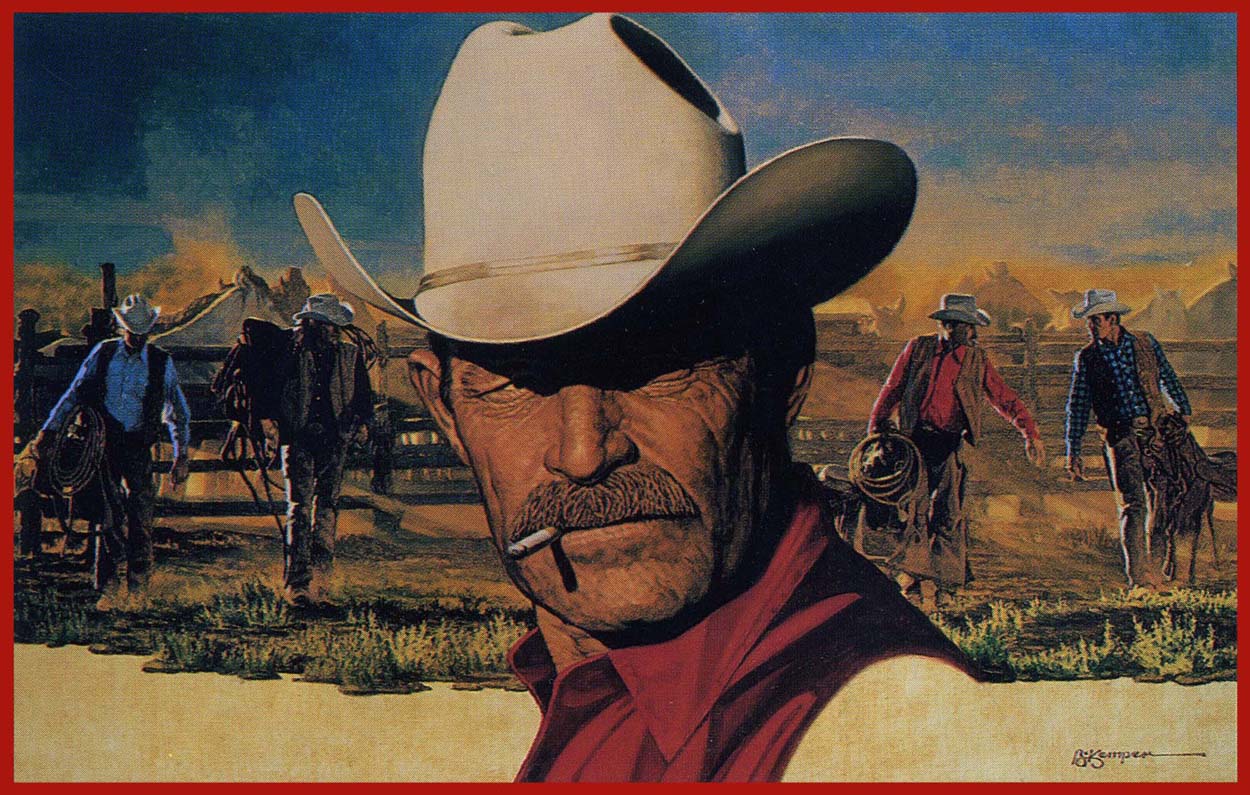

Knowing that smoking was not so much about cigarettes as it was a personal identification with the brand, Phillip Morris knew a good rebranding was needed. He needed a personality that would render health concerns and girly connotations irrelevant; a masculine, life weary individual with a who gives a fuck attitude. What American icon did he think best symbolised such traits? The cowboy.

And so the Marlboro Man was born, a figure that embodied, more than any other single figure in Western culture, the personality of smoking. Said Morris, “The Marlboro man is alone. He is reflective as he relaxes with a cigarette. There is masculinity, and I would even say moodiness, rather than just mood – although not fickle moodiness.”

What the Marlboro Man campaign demonstrates is advertisings ability to latch on to popular culture and use its symbols and meanings to sell products. This is the merchandising of metaphors that already exist in our culture, using them to capture the public’s imagination and offer individuals tangible ways to assert their identities.

Though smoking advertising has been banned in many countries, the powerful symbol evoked by the Marlboro Man, and reinforced still through popular culture, endures. That is not to say that anti-smoking ads and initiatives have not been successful. Smoking rates in most Western countries have plummeted, thanks in no small part to anti-smoking campaigns.

But it a testament to the Marlboro campaign that smoking endures at all. Despite widespread awareness that smoking kills, it's still a habit that appeals to people, particularly the young, as a way to express their individuality, power and rebellion. It appeals to men as the ultimate symbol of strength and masculinity, to women as a form of liberation and rebellion.

The very fact that society has launched such an all-out assault on the evils of smoking has, in many ways, lent to the smoking identity. Perhaps smokers today are less the cowboy fighting against the harsh wilderness, and more the misunderstood outcast rebelling against the tyranny of public health. Their battle is different, but they are still cowboys at heart.

Next week I’ll look at the flip side of the coin – the power of anti-smoking campaigns.

Beth Gibson