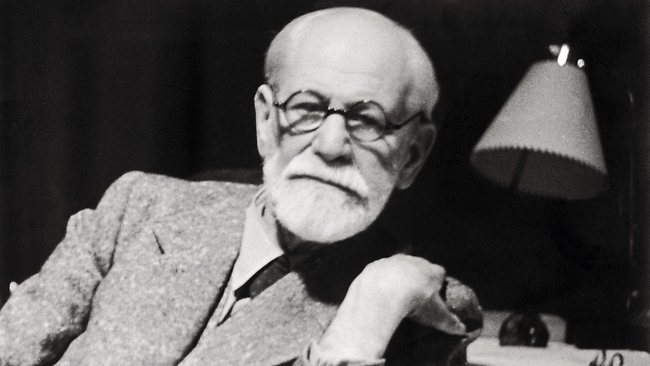

Sigmund Freud was certainly a little strange. When I studied psychology briefly, the Viennese psychoanalyst was discussed in one lonely lecture, before we were firmly told: “Freud will not be relevant to the remainder of the course, as his theories are largely discredited by modern psychology”.

This saddened me, because I thought Freud was pretty interesting. No doubt, many of his theories seem odd at best, embarrassing at worst. Among the most amusing are the Oedipus complex – all men want to marry their mothers and kill their fathers – and penis envy, which argues that all women feel psychologically “castrated” and long to have male genitalia. I would just like to say that I have never wished for a penis, though I’m sure Freud would argue that not only do I without-a-doubt have penis envy, but I’m also hopelessly repressed about it.

But at the crux of many of Freud’s theories is one particularly interesting insight into human nature, which not only spurned the industry of psychoanalysis, but has also profoundly influenced the world of advertising and public relations.

Freud believed that people are, at heart, irrational creatures. Our most powerful driving forces are sex, power, and security; rather than reason. Society, then, serves to control these innate desires so we can coexist more rationally and productively. The animal kingdom, on the other hand, is a place where desire rules.

At around the time Freud was formulating these ideas, the producers of American goods were experiencing a problem. It was industrial boom time and an abundance of goods were being made, but consumers had yet to develop a hyper-consumerist mindset. Demand wasn’t meeting supply.

Part of the problem was that products were still advertised for rational reasons – like durability and quality – rather than emotional ones. People were too easily content with perfectly usable stoves, cars, and televisions. How then, could one encourage the higher rate of consumption needed to meet supply and stimulate the economy?

Luckily for America, Freud had a cousin called Edward Bernays, who has since earned the title “father of Public Relations”. Bernays took Freud’s idea and applied it to consumers. If desire is our driving force, then appealing to emotions is the most powerful way to persuade consumers to act. The idea was to short circuit their rational conscious and get them where they were most vulnerable – the unconscious.

One of Bernay’s most successful attempts at this was encouraging women to smoke. In the 1920s female smoking was taboo. Women could only smoke in certain designated areas, or not at all. If caught doing otherwise, they would be arrested. The president of Lucky Strike wanted to expand his consumer base, and asked Bernays to help him tap into the female market. Bernays consulted a psychoanalyst who told him that women saw cigarettes as a symbol of male power.

adobe creative suite

This insight led to the torches of freedom campaign in 1929. As part of an Easter parade, women were encouraged to light up a cigarette and march for women’s rights. The event got national and international coverage, and rates of female smoking skyrocketed. Bernays had successfully taken a product that, in reality, gave women no real liberation, and had linked it instead to the feeling of empowerment. Smoking has been a symbol of female rebellion and power ever since. (Bernays was said to have later regretted this campaign after his wife died of cancer.)

Bernays almost single handedly created the public relations industry, pioneering techniques like celebrity endorsement and promotional events. His personal ideas about consumers, however, were something else entirely. Bernays believed that a “real” democracy in which humans were truly free was impossible, because the irrational drives of the common man would threaten social order unless controlled. By linking consumer goods to these desires, consumerism could be used to superficially satiate people, thus ensuring the common man remained docile. And because goods could never truly satiate deep primal needs, people would never stop buying, thus ensuring a constantly thriving economy.

While that may seem a bit extreme, Bernays use of Freud's theories has much relevance to advertising today. In a world where there are a vast number of very similar products, and all our base needs are overly satisfied, creating a personality for a brand that consumers can emotionally connect with has never been so important. What’s more, companies are constantly coming up with new products, ones we didn’t previously realise we needed (vitamin water, anyone?). A successful advertising agency then, according to the Austrian psychologist Ernest Dichter, “manipulates human motivation and desires and develops a need for goods with which the public has at one time been unfamiliar – perhaps even undesirous of purchasing”.

You might be reading all this and thinking: what crap, I buy things because I want to, not because I’m emotionally manipulated into buying them. And in many ways, you could be right. Products are sold for a whole host of reasons, many of them practical. What’s more, buying a dress because you want to feel attractive seems, on the surface at least, perfectly reasonable.

But it’s worth thinking about all the same. Why did I buy that dress? Did I really need it, or was I trying to fulfill some deeper need for social acceptance, or love? And perhaps the more important question: does a dress really have the ability to fulfill a deep longing for love or worth in the eyes of my peers? Can an external thing fulfill an internal need? How long until I feel dissatisfied again, and need another product to make me feel worthwhile?

Next week: as the election approaches, let’s have a look at political advertising. A new way? Choose real change? What do those slogans even mean? What are the tricks and tactics used by our politicians to persuade?

Beth Gibson