I was once having an argument with a friend about whether beauty products, and the advertising that sells them, were good or bad. I took the latter stance, but he thought differently.

What was wrong, he argued, with a woman putting on a bit of mascara in the morning? Surely if it gave them some confidence and a lift, then that was a positive thing? And how exactly was beauty advertising manipulative? Isn’t it that the women who don’t care for makeup aren’t affected, and the women who like makeup buy it regardless of advertising?

I never got the change to reply, but it’s a conversation I’ve thought about a lot since. That’s because, though I don’t like to be dogmatic about the evils of advertising, beauty advertising is one area in which I tend to, for lack of a better phrase, lose my shit.

My position is complicated by the fact beauty products have been reclaimed by some feminists as tools of empowerment rather than oppression. I’m not sure many feminists are desperate to reclaim beauty advertising anytime soon, but non-the-less, most products are not evil in and of themselves. They’re just another thing, and makeup can also be a tool for both creativity and self-expression.

But what can be problematic are the ideas and techniques used to persuade us to buy makeup. Like, really problematic. So I decided to use the blog this week to deconstruct my friend’s argument and articulate what it is about beauty advertising that drive me nuts.

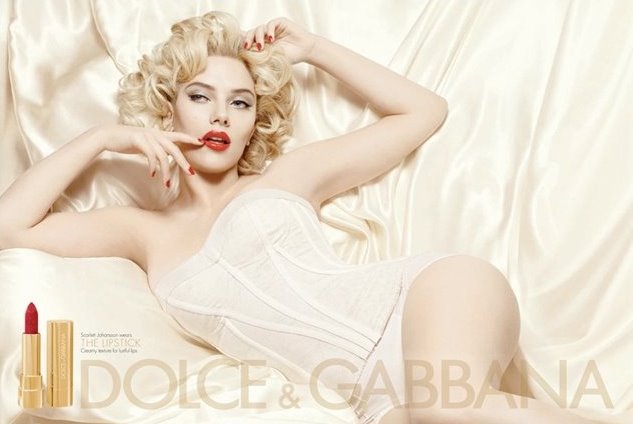

Firstly, beauty advertising often has little to do with the product. The product is usually dwarfed by an enormous image of a beautiful woman. This is because what beauty advertising is selling you is not a product in and of itself. It’s selling you beauty, and more specifically, the happiness, self-worth and love associated with beauty. This is why celebrities are increasingly used to sell beauty products. Celebrities, after all, represent our best selves – they are beautiful, successful, and adored by millions.

Advertising tells women: Buy this mascara and you will be as happy as this beautiful woman. This message leads them to believe that their worth is inextricably tied up with their appearance. That what will bring them happiness is being attractive, particularly in the eyes of men. That who they are as a person is secondary to the level of psychical beauty they can achieve.

And here’s where it gets particularly nasty. Not only do beauty ads sell the idea that beauty equals happiness, they also ensure that this marriage of beauty and subsequent happiness is unattainable. That’s because, if products provided you with any genuine, long-lasting sense of happiness, companies would go out of business. The need you to keep buying. They make their best bucks off ensuring you are permanently discontent and are constantly seeking to remedy this by buying products.

As American historian Christopher Lasch once said, advertising “seeks to create needs, not to fulfil them; it generates new anxieties instead of allaying old ones.” Cosmetic companies are constantly creating new products to fix new beauty problems we didn’t realise we had. They sell us mascara, but when we get too content with that, they tell us that what we now need is volumising mascara, or lengthening, or smudge proof, or anti-clumping, or mascara with glittery bits in it. Oh, and eyeliner too. In every colour. Quick, go shopping! Before you get ugly!

Consequently, women are made to feel like they constantly need to go to greater and greater lengths just to be considered, at the very least, acceptably attractive. One minute all you need to be beautiful is a bit of lipstick, the next, your completely disgusting if you don’t wax all the hair off your genitals. It’s got nothing to do with any real, objective concept of beauty, and everything to do with companies making money. Lot’s of it.

To ensure this beauty ideal stays unattainable, images used are meticulously airbrushed and photo-shopped. Even models, as close to embodying the beauty ideal as human women can get, are not perfect enough. Cindy Crawford once said, “I wish I looked like Cindy Crawford”. That’s kinda fucked. Two years ago, the below L’oreal ad, featuring Julia Roberts, was banned. Julia Roberts face had been viciously altered, and the Advertising Standards Authority ruled the “adverts misrepresented what the products could do to a normal face.”

And what of those women who aren’t interested in beauty products? Are they safe? Well firstly, the whole point of advertising is to persuade people to do things they might not otherwise do. Companies wouldn’t spend $200 billion a year preaching to the converted. What’s more, advertisements are omnipresent and pervasive, constantly bombarding us with messages that are very difficult to avoid.

What’s more, these messages are urging us to conform. They tell us that if we don’t at least try to be beautiful (with the aid of products), that we are ugly, failures, unlovable. These are things most people do not want to be, whether they think makeup is a waste of time or not. All these factors make the beauty ideal very difficult to resist.

At this point, I’d predict my friend my argue something like this: Yes, it’s bad to make women think that an unattainable ideal of beauty is essential to their self worth, but still, what’s wrong with the girl who gets a little lift from a coat of mascara in the morning? What about the women who like makeup, who would have bought it regardless of advertising? Here’s where things get a bit subjective and tricky, but for the sake of argument, I’ll give it a go anyway.

We are not born needing makeup. We are taught, somewhere along the line, that our natural selves are not good enough, that we need to alter our faces and bodies from their natural state to be considered acceptable, or, if we are lucky, beautiful. If all women stopped wearing makeup, would men around the world simultaneously get turned off and vow never to sleep with a woman again? It’s biologically doubtful.

Rather, women might find themselves with a lot more money and time on their hands. Time to nurture their internal selves, rather than their external selves. Because the idea that an external thing – beyond essential needs – can satisfy internal hungers like love and acceptance seems paradoxical. And whether or not this utopian vision is feasible, or even desirable, I can almost guarantee that cosmetic companies would be pretty pissed off about it. That, and bankrupt.

Beth Gibson